When my first novel was being copy edited, I wasn’t terribly concerned. I’m a good speller, and spell-check finds any little typos, right? I also felt I had a pretty strong grasp on grammatical conventions. Piece of cake, I was thinking.

Oh, how I hung my head in shame when the edits came back.

As it turns out I am a, shall we say, creative hyphenator; I can’t seem to get the difference between homophones like brake and break; and I blithely flout the “verbs of utterance” law.

Come on, admit it. You’ve never even heard of verbs of utterance. Lord knows I hadn’t, and I was kicking their little typeset butts all over town. (More on that later.)

I was embarrassed, and wondered what my editor must have thought when she saw all those errors. Consciously or subconsciously, people make judgments. The way we communicate gives off signals—sometimes inaccurate ones—about how smart, professional, conscientious, etc we are.

Besides, we’ve all seen typos in books, and it’s distracting. It takes you out of that sweet reverie of this is real, and reminds you that someone who spends way too much time alone and indoors cooked it up. Might a potential agent or editor enjoy a manuscript less—and even reject it!—if she keeps getting distracted by errors? I have to believe the answer is yes.

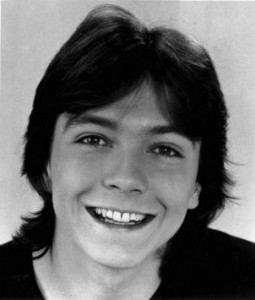

Since then, I’ve tried hard to master the grammar and spelling I seemed to have missed in fifth grade when I was too busy thinking about that cute boy with the David Cassidy haircut two rows up.

I recently asked some author friends about their editing-related Achilles heels.

Catherine McKenzie: I like to use that saying “a little” too many times. I do word searches at the end of manuscripts to remove them. Scary results.

Allie Larkin: I overuse “just.” And peek/peak is one of my problems. On the other side, I always have to correct copy editors on German Shepherd. They tend toward lowercase S, like it’s a shepherd that happens to be German, when it’s a shortened version of the official breed title: German Shepherd Dog (all starting with caps).

Ann Mah: Toothsome. Not only have I overused it, apparently it doesn’t mean what I thought it did. Yikes. Forever banned from my vocabulary.

Randy Susan Meyers: I seem to slip in and out of the Oxford comma, which I am certain drives my copy-editor bonkers.

Judy Merrill Larsen: I am completely incapable of using lie/lay correctly, so I try to avoid it at all costs.

Katherine Howe makes no grammatical errors. In fact, in the course of the above conversation, she explained both the Oxford comma (also known as the Harvard comma) and the lie/lay conundrum, for which we were all quite grateful.

For your self-editing pleasure, here are a few rules which writers often unwittingly break (or was that brake?)

Verbs of Utterance (You were waiting so patiently for this.) Some verbs can be used in place of “say” and some can’t. To my mind, the list is fairly arbitrary, but still, there is a list (somewhere, I’ve never been able to find an official one), and you should generally know what’s on it. For instance, you can chortle a sentence but you cannot chuckle it. I’m not kidding. You can cry a sentence but you cannot sob it. Another big no-no is “sigh.” No one can convince me you can’t sigh words like “Oh, dear,” but nevertheless, it’s not legal.

Hyphens There are a lot of types, a lot of rules, and a lot of exceptions. But here’s one guideline that really helped me. In a phrase like “blood-red moon” generally there is a hyphen if the first descriptor modifies the second. Blood describes the kind of red, not the moon. However, if the noun comes first, you don’t use a hyphen. “The moon was blood red.” Red is the only thing left for blood to describe so the hyphen is unnecessary. In a phrase like “skinny, old nag” both skinny and old describe the nag, so you use a comma, not a hyphen.

Ellipses are used for a pause in speech, for instance when the speaker is hesitant to say something. “I loved him … but I didn’t always like him.” Insert a space after the first phrase, then three dots, then another space, then the second phrase. They can also be used to convey that there is more that isn’t being said at all. “Her alibi seemed highly unlikely ….” Notice how I used four dots because it’s the end of a full sentence.

Oxford/Harvard Comma When making a list, Oxford/Harvard says you put a comma before the and. “I bought toothe paste, grapes, and a hunting knife.” Or your can do it without: “He eats nothing but candy, cumquats and caviar.” What you shouldn’t do is switch it up over the course of your manuscript. Pick your comma convention and stick to it.

Lay/Lie It’s all about who or what is descending. You lie down. You lay other stuff down. Think of “lay an egg.” The past tense of lay is laid. So the hen lays an egg today and laid one yesterday. Pretty straight forward. What makes everyone nuts is that the past tense of lie is lay! So, you lie down now, but you lay down yesterday. Come on, who’s responsible for this stuff!

It would be nice to think a potential agent or editor would simply look past bad grammar and misspellings to the fabulous prose you’ve sent them. But if they’re on the fence and your work looks sloppy and unprofessional, it could be the thing that makes them say, “Nah,” and pick up the next person’s manuscript. It’s worth it to tidy up those messes and give yourself the best possible chance.

What are your favorite grammar crimes?

(Photo credit: Wikipedia. Publicity photo of American actor and musician, David Cassidy promoting the September 25, 1970 premiere of the ABC comedy series The Partridge Family.)

I found this so helpful, as well as quite humorous. Thanks for the lesson,